I embarked on the journey of taking this course on

contemporary food activism from a humbled and somewhat naïve perspective when

it came to food. I had only been introduced to Monsanto in October, and had no

idea what the hype was about organic food, other than that it sounded cool and is commonly associated with what our generation calls “hipsters.” Upon

completing this course, and specifically through my weekly blogging of issues

relating to how food and food activism contribute to the construction of

identity on both the individual and communal levels, I have learned an

incredible amount. Not only did I gain new insights into pressing issues surrounding food and its

production and distribution, but I was also able to consistently reflect on my own habits and identity as a

consumer.

Throughout the course of the semester, I have come to

understand that the category of food activism is more multifaceted than I

initially anticipated. In focusing specifically on the effects of food

consumption and activism on the formation of identity and community, I have

also arrived at the conclusion that food activism’s effects on identity are

just as multidimensional. While the thought of food activism used to conjure

images of small farms and lab coat-clad scientists conducting research on

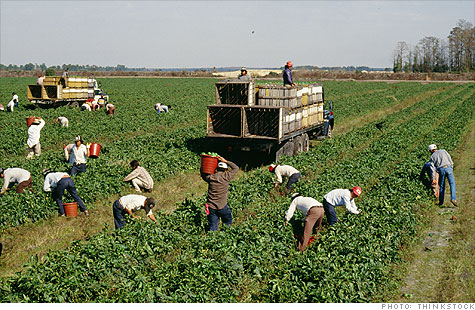

seeds, it now evokes thoughts of labor and immigration policy issues, political protests, the historical role of agrarianism, the glorification of the farmer

using popular culture, and romanticized farm tourism. Ultimately, my exposure

to these less prominent facets of food activism in the 21st century,

both from a broader perspective and through the lens of food’s impact on

identity (the focus of this blog), has allowed me to examine their associated discourses and apply them

to my own practices and beliefs as an increasingly conscious citizen.

From this class, I’ve learned that food is historical.

Though our course is entitled “New

Food Activism,” it’s easy to forget that the trendy tendencies to choose Whole

Foods over Stop and Shop or desire to work on a farm after graduating from a

pricy liberal arts college have roots (pun intended). The definitions of

concepts commonly associated with contemporary food activism, ranging from

‘farming’ to ‘industrial agriculture,’ largely hinge upon how they were defined

decades ago, along with how reactions to such definitions led to the large

back-to-the-land movement experienced today. From a brief engagement with

Pollan’s The Botany of Desire, we

learned that each food has a past, a concept that I applied to my own

understanding of the onion that has made my home region, the black

dirt-rich Hudson Valley, famous decades ago.

Food is also global. I was particularly moved by our class

discussion of the controversy of quinoa in the increasing distress it places

for its Bolivian growers, as well as PETA’s response to this alarming article,

revealing divergent opinions on the prioritization of food issues across the

globe. Through my pioneer blogging experience, I also witnessed how the impact

food has on identity is global—in Morocco, I observed vegetarian friends

struggling with the dozens of questions and puzzling looks they received about

their food habits, as well as how meat eating was foundational to many Moroccan

traditions and religious rituals. Through a dissection of the concept of terroir both in the classroom and

online, I’ve encountered the idea that food is directly connected to a sense of

place, which is often strongly associated with nostalgia, and is a subsequently

prominent factor in constructing both individual and national identity.

And yet food is incredibly personal. My local onion represents a symbolic portion of local identity largely embodied

by middle class residents and simultaneously incorporates the transnational identities of the

immigrant farm workers producing such a ‘local’ entity. In class, we hashed out

the ways in which ideas of the local are romanticized, relating to our

discussions with Patti Close of Tufts Dining Services and local farmers. Like

the onions of the Hudson Valley, Boston's Haymarket, which we

visited and discussed, also

exemplifies how global identities have fused on the basis of food to become

local. Thanks to capitalism, different markets have revealed their attempts to

exploit the recently popular concept of the local, in ways like selling home

gardening supplies (evidenced by my Groables post) and making

small-scale farmers sexy again (like in my posts about the Dodge Superbowl commercial and farmer-based dating sites). In attempting to focus

more exclusively on the local, global markets and groups have converged on

different ideas of the local, which affects the ways in which consumers, myself included, construct their own senses of local as part of their identities.

I've learned that food is cultural, and even racial. Through reading Slocum’s

piece on the cultural appropriation and hierarchical arrangement of food and

viewing promotional films like that of “Dean’s Beans,” I’ve

witnessed how food can be used as a medium for highlighting difference on the basis of ethnicity and race. As our Haymarket guide noted, there are many events and locations in which foods

and ethnicities comingle, creating spaces for both multiculturalism and a

cohesive identity on the basis of food. In addition to bridging the

gap between different cultures interacting in one place in the presence of

food, food is also embodied by the culture in which it is consumed and

discussed. With J. Crew’s “The Naturals” line, the idea of sustainable food as

trendy manifests itself in eco-chic clothing, revealing how food can also be

culturally appropriated. The concept that food is cultural also has the

potential to connect with food as indicative of class, evidenced by our

discussion of terroir and tastes of

luxury as associated with place and context. Ultimately, food is

both produced by the interaction of various cultures and identities, but also

actively contributes to further cultural production.

Food is not always gender neutral. In addition to our

discussion of the female domination of the current back-to-the-land trend,

which was supplemented by visits from female farmers and activists, my reading of Carol Adams’ The

Sexual Politics of Meat illuminated the idea that men and women are not approached equally through the lens of food. In both my overall review of

Adams’ book and blog post about applying Adams’ theory of the parallels between

feminism and vegetarianism to the use of meat-based names to identify male genitals, I explored how food allows us to look at men and women in different lights. This is perhaps because of the ways we approach and treat animals to be

used for food, exemplified in Adams’ discussion of the sexual mistreatment of cows in the dairy industry. The role of feminism in new food activism is

reflective of both this argument that mistreatment of women is connected to the

ways we treat animals and the historical prominent role played by men in the

agricultural industry. While new food activism seems to focus on catalyzing change, moving away from capitalism and industrial agriculture, the

pinnacle role of women in such efforts seems to be revolutionary in and of

itself, and such a revelation has impacted how I identify myself as a female consumer and activist.

Food is, of course, biological and environmental. Our

discussions of biopower and man’s domination of natural resources seem to be at the foundation of all food production, and yet they

also point to another way in which food activism contributes to identity. I

learned that the desire to feel attached to the physical land and, as many of

my classmates have put it, “get your hands in the dirt,” is a quintessential

element of the back-to-the-land movement. I got an especially strong sense of this

trend both through our workday at a community garden and in hearing

Amy Franceschini discuss her “Soil Kitchen” project, in which biology met

community as locals swapped soil samples for soup. Though the environmental

characteristics of food are obvious, they are also intricately connected to the

ways in which food shapes our identities through social, historical, and

economic processes.

And on that note, food is social. Above all other factors,

the communities built around food appear to represent the most profound

characteristic of contemporary food activism. Ranging from a classmate’s

discussion of how food brought people together in the Occupy Boston encampments

and the solidification of the local community in the film “The Garden” to

spaces of food exchange that unifies consumers like Haymarket and Soil Kitchen,

the social force of food activism is undeniable and prominent. As explored in

my first blog post, the social communities created by food represent a wide

spectrum of global and local, digital and personal, and urban and rural groups

that have formed around common goals involving change in the consumption of

food. I have observed how such communities, big and small, have the

potential to impact how we construct our identities as consumers.

Food is political, and the politics associated with food

often dictate its ability to foster communities, as I just described. In

viewing “The Garden,” I understood how the future of a particular community

that had been formed on the basis of a common space and approach to growing food

could be placed in the hands of lawmakers and politicians. Politics directly

related to corporate control of agriculture was a hot topic of discussion of

the Occupy Boston movement, as discussed by a classmate, and the livelihoods of

the migrant farm workers responsible for the cultivation of onions native to my

home region of New York are directly determined by local and national politics.

Despite the widespread contemporary desire to shift consumer focus to local

food, it has become evident through both classroom discussions and research for

this blog that some type of politics will always dictate the ways we engage

with our food and consequentially how we shape our identities on the basis of

food and food activism.

Food is economic. Just as it is ironic that national

politics have the potential to permeate the trend and desire to turn to local

food, there is tension between the fact that food activists are dissatisfied with the corporate domination of agriculture and

the notion that it takes significant capital to be able to go “back to the

land.” I am still

struggling with this romanticized vision of leaving a private college to work in the dirt, for the fact that such a

decision reveals a certain amount of privilege seems to

conflict with the notion that farming is removed from the capitalist

environment of the big city. I also wrote in several blog posts, including those about Groables, Farmers Only and organic clothing lines, about the

irony existing in the fact that the very corporations these back-to-the-land

enthusiasts and activists are attempting to avoid are successfully capitalizing on this desire to be more local and green. Whether food is consumed locally or

internationally, capital is involved, and the honest truth is that money is the

factor around which we, as both consumers and a nation, make plenty of

decisions regarding food.

But what is most impressive about all of these different aspects

of food is that they are all interconnected, as are their similarly

multidimensional effects on identity, shaped through food. While dragon fruit

in Vietnam is both historical and highly political, the connection between meat

and women as facilitated by Carol Adams is gendered, social, and historical,

all in one. My local New York onions are historical, personal and symbolic, and

yet those responsible for their growth represent migration on the global scale,

as well as the politics surrounding US immigration. I have been able to apply

my understanding of the interconnectedness of aspects of food activism to one

particular component, that of identity and how food fosters community, and I

have witnessed how the same interconnectedness is also prominent in a zoomed-in

examination of how food shapes identity. After a semester's worth of food-related discussions, I'm definitely hungry, but now I know that going forward I will be even more conscious of what I choose to put in my mouth and how my food choices shape my identity as a consumer.