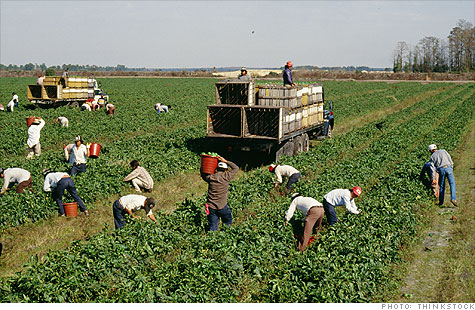

In light of a recent class assignment, which entailed bringing in a food item of choice in its raw form and discussing the politics we perceived to be surrounding this food item, I have seen more of a connection of my hometown to new food activism than ever before. My selection, a simple onion, represents the famous Black Dirt region of New York's Hudson Valley, which is not only regarded as one of the richest farmland regions left in the US but also as the supplier for over half of New York's onions. My preparation for this discussion of the politics of this onion involved refreshing the memories of hearing my father's stories from when he spent his summers laboring beside Spanish-speaking farm workers in the black dirt, my own experience volunteering for the health clinic serving these workers, and the food on my table at home in upstate New York. To the neighbors and consumers of Hudson Valley produce, the onion represents a symbolic staple of the region associated with a specific class of workers--that of migrant farm workers, the vast majority of whom are Spanish-speaking. But for the laborers without whom these onions wouldn't exist, such a piece of the earth symbolizes a source of income, but also a community, a lifestyle, and an identity.

Gaining experience by working alongside these healthcare workers, most of whom had been undocumented immigrants at some point themselves, not only illuminated the lifestyles of the thousands of migrant farmworkers in and around my town, but also made me more aware of assumptions and stereotypes pertaining to this community held by many residents of my area. I was horrified to hear that my father, as a local police officer, had heard of other local authorities referring to all of these workers as "Mexicans," assuming that their accents, appearances or apparent occupation meant that they could have only originated from one country. The vicious stereotypes that circulate my town, which is neither notably conservative nor unfriendly, also dictate local politics on immigration law--the presence of these local farmworkers, many of whom reside in the lower income areas of my town, have provided a personal face for this national issue. These workers are blamed for unemployment, crime, visible traces of poverty, language issues, and educational barriers, and yet without them, we could not have the 'local' produce that is so desired by many consumers nowadays. In this sense, my onion is political.

After several weeks of volunteering abroad in Rwanda, I experienced an eye-opening transition in immediately beginning my internship with the Alamo Health Center site of Hudson River HealthCare and the neighboring Farmworkers Community Center upon my return. I was surprised to encounter as many parallels between the developing nation I flew halfway across the world to dig into (pun intended) and the farms in my backyard, and I immediately felt guilty for never having explored this rich community resting quietly beneath my nose for the past twenty years. As part of my internship, I ventured into the camps of these migrant farmworkers in order to deliver educational presentations in Spanish relating to farming-based health and safety issues. Through this experience, I was the one who ended up learning the most. Not only did the daily labors of these farmworkers shape their individual identities, but they also fostered a stronger sense of community than I could have foreseen. After a few weeks of working at the clinic, I was assigned the task of arranging community fitness events that would bring together these migrant families in order to combat the high rate of diabetes and obesity observable in their community. It was through experiences and interactions like these that I witnessed how this region, symbolized by my onion, represents a community within a community, and that the produce emerging from the Hudson Valley is emblematic of such relationships. On my last day at the clinic, one farmer presented me with the gift of a heavy bag of onions, revealing not only his unfailing kindness but also the deep symbolic role of the onion as a food illustrative of the cultural and traditional values held by these community members. The interaction of these numerous facets of society within this region, ranging from the political to the cultural, is indicative of the fact that the community giving life to this local produce is as rich as the black dirt from which it emerged.

So yes, the onion is political. But from my experiences, I have learned that the onion, my Hudson Valley onion, is also social, historical, and cultural. It is a symbol of my father's past and my family's present and future, the workers I've met, how far they've come and how far they still have to go, how much I gained from working and learning in my own backyard, and a personal approach to the meaning of 'local.' The symbolic value of the onion, just as with any food personally associated with the 'local,' is just as layered as the onion itself, revealing the complexities of the movement towards localizing produce as part of contemporary food activism.

No comments:

Post a Comment